KAMPALA, Uganda (AP) — The deadly march by Rwanda-backed rebels across eastern Congo could widen into a regional conflict drawing in even more countries, analysts warn, and two neighboring nations with the most involvement in the mineral-rich area might be the key to stopping the violence.

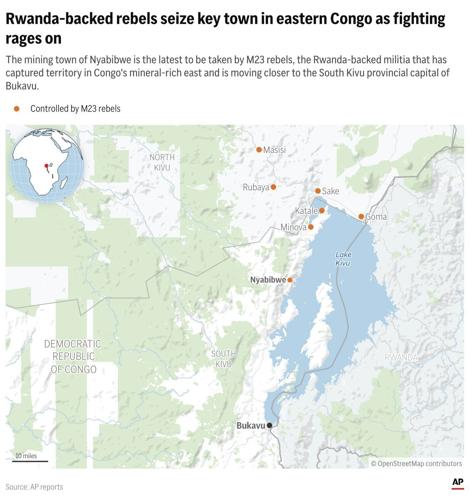

The ' capture of the city of Goma last month and their reported advance on another provincial capital have drawn in concerned countries from east and southern Africa. A of leaders from those regions over the weekend offered no strong proposals for ending the fighting beyond urging talks and an immediate ceasefire.

Notably, they didn’t call for the rebels to withdraw from Goma.

At the summit’s conclusion, Congo issued a statement welcoming its “foundations for a collective approach” to securing peace. But there are concerns that long-shifting alliances in the region also could lead to a collective collapse.

Asking neighbors for help

Congolese President Felix Tshisekedi had sought the help of allies in the region and beyond when the M23 rebels resurfaced at the end of 2021.

Troops from Burundi, with its own tense relations with Rwanda, were sent to fight alongside Congolese forces. Troops from Tanzania, which hosted the weekend summit, were deployed in Congo under the banner of a regional bloc. And Uganda, on poor terms with Rwanda, had already deployed hundreds of troops to fight a different rebel group in eastern Congo.

For Congolese President Felix Tshisekedi, it was “like juggling a polygamous marriage” as he maneuvered to protect his vast country's territorial integrity, said Murithi Mutiga, Africa director at the International Crisis Group.

“Rwanda felt excluded while Burundi and Uganda were welcome” in eastern Congo, Mutiga said. “Rwanda decided to assert itself.”

A surge in fighting

Congolese authorities see the M23 rebels as a Rwandan proxy army driven to illegally exploit eastern Congo’s vast mineral resources, whose value is estimated in the trillions of dollars.

The rebels are backed by some 4,000 troops from Rwanda, according to evidence collected by United Nations experts.

The M23 rebellion stems partly from Rwanda’s decades-long concern that other rebels — ethnic Hutus opposed to Rwanda's government and accused of participating in Rwanda's 1994 genocide — have been allowed to operate in largely lawless parts of eastern Congo.

Rwanda's longtime President Paul Kagame accuses Tshisekedi of overlooking the concerns of Congo's ethnic Tutsis after hundreds of thousands of Tutsis were killed in the genocide.

The M23's ranks contain many Congolese Tutsis.

The rebels’ next big target is Bukavu, capital of South Kivu province, and they have to Kinshasa, Congo's capital, some 1,600 kilometers (1,000 miles) away.

Risk of more armed actors

Eastern Congo in recent decades has been the setting for a conflict that has caused the highest death toll since World War II.

Its last major regional upheaval broke out in 1998 as Congo's then-President Laurent Kabila invited forces from countries including Zimbabwe and Angola to protect him from Rwanda-backed rebels who sought to overthrow him. Uganda and Rwanda, which had helped Kabila seize power by force the previous year before feeling alienated by him, fought mostly on the same side.

Now, analysts say both Rwanda and Uganda are key again.

The risk of regional escalation this time is "big,” especially with both Kagame and Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni still eager for influence in eastern Congo, said Godber Tumushabe, an analyst with the Kampala-based Great Lakes Institute for Strategic Studies think tank.

Both leaders are crucial to any effort to stop the fighting, Tumushabe said: “They will not allow a settlement” that doesn’t look after their interests in eastern Congo. But they have their own friction as Rwanda suspects Uganda of backing yet another group of rebels opposed to Kagame.

Burundi is also heavily involved. A year ago, Burundi closed border crossings with Rwanda and severed diplomatic ties over allegations that Rwanda’s government was supporting rebels in eastern Congo who oppose Burundian President Evariste Ndayishimiye. By then, Burundian troops were deployed there to fight alongside Congolese troops.

Ndayishimiye has accused Kagame of reckless warmongering. He told a gathering of diplomats in Bujumbura last month that “if Rwanda continues to conquer the territory of another country, I know well that it will even arrive in Burundi.” He warned that the “war will take a regional dimension.”

Efforts at peace

With Rwanda and Congo each "drawing a line in the sand,” diplomacy faces a great challenge, said Mutiga with the International Crisis Group.

Efforts at peace have largely sputtered, including the yearslong presence of a U.N. peacekeeping force in eastern Congo that has been under Congolese government pressure to leave.

Other fighters on the ground have included mercenaries for Congo, including many Romanians, and troops from the southern Africa regional bloc that Rwanda's president has alleged — without providing evidence — are not peacekeepers but collaborators with Congo’s army.

Congo's president has refused to engage with the M23. And he did not attend the weekend summit in Tanzania, instead monitoring it virtually. At its conclusion, his government welcomed the collective effort to stop the fighting but disputed Rwanda's attempted explanation for M23's resurgence.

"The current crisis is, above all, an attack on (Congo's) sovereignty and security, and not an ethnic question,” Congo's statement said.

The next steps in trying to resolve the conflict are unclear.

____

Associated Press writer Gaspard Maheburwa in Bujumbura, Burundi, contributed.